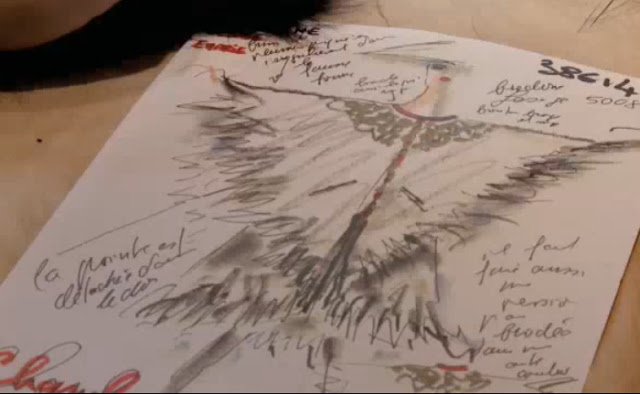

Sketch of cape for Chanel F/W 2009.

We might have expected a return to minimalism. Simple lines, earth tones, basics. After all, simplicity is often associated with lean economic times. It was no coincidence that during the 1990s, the height of fashion minimalism coincided with five major international financial crises. The domino collapse of asian currencies in the late 90s may have been the best thing that ever happened to Helmut Lang, and Cathy Horyn certainly had a point when she said that 'to some extent, we associate minimalism with failure'. When an economic crisis hits, minimalism makes sense: it's fairly obvious that when you're living from paycheck to paycheck, you're not going to blow your budget on crystal knuckledusters.

So in the late 00s, in the wake of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, we might have expected trends to tend toward sobriety. Instead, we saw the opposite. Shapes, colours, and materials grew more and more extreme. Shoulder-pads shot off like missiles, boots inched up the thigh, the ubiquity of rare furs and skins gave PETA a protracted migraine, and Chris Decarnin, appearing out of nowhere in an explosion of studs and spangles, was proclaimed the new chieftain of the übercool. Fashion-lovers who lacked the capital to keep up wept at the sight of that Balmain military jacket, knowing that try as they might, Zara wouldn't come up with anything comparable.

Balmain Spring 09 RTW

Balmain Spring 09 RTWIf we look back on fashion trends over the last few years, the tendency toward exorbitance makes us wonder: how exactly did this happen? Even those of us who have the self-control to keep the credit card locked away have secretly found ourselves thinking, 'If I just give up food for a month, I can afford those studded Pigalles!' Indeed, at the start of the financial crisis in 2007, the fashion world was hurting. Sales plummeted and the formerly unflappable elite of the industry began searching for ways to persuade people to shop, tapping into new technologies like twitter and facebook to promote spending. A decade ago, could we ever have imagined Anna Wintour setting foot in Macy's, let alone Queens? And yet the editor of American Vogue put on her game face in 2009 and ventured into the borough to launch the Fashion's Night Out initiative: a gimmicky evening where B-list celebrities and models hung out in designer stores in order to send the message that 'It's ok to shop again.'

But fashion's longterm battleplan against the economic downturn has been even more insidious and ingenious than we may initially have thought. It turns out that the industry's most effective weapon lies in its very nature; its ability to shape the consumer psyche. Instead of allowing women to dig through their closets for pieces that could adapt to new trends, the fashion industry reacted to the economic crisis by making it basically impossible to be a spendthrift. In the face of trends that had evolved far beyond anything we already owned, the message rang out loud and clear: if you want to be relevant, you are going to have to buy. And it worked. As consumers turned a blind eye to their hemorrhaging bank accounts, the cleverest retail companies reported staggering increases in sales (etailer Net-a-Porter's pre-tax profits grew by 234%).

Natalie Massenet, founder of Net-a-Porter.com

Fashion is a formidable economic force for a number of reasons. For one thing, it successfully targets one of the largest and fastest growing markets in the world: women. A recent study by the Boston Consulting Group anticipates that over the next five years, total female-earned income will grow by $5 trillion. Newsweek reports that this massive growth will make women the 'biggest emerging market in the history of the planet--more than twice the size of the two hottest developing markets, India and China, combined.'

Fashion also has a unique capacity for change and can therefore adapt to different economic climates faster than Heidi Klum can say 'you're out.' New, mobile production facilities enable clothes to be made as they are shipped so you can buy your H&M chain dress only days after it appeared on the runway at Ungaro. Google, eBay and Fedex make it possible to find virtually any article of clothing you desire and have it shipped overnight into your hot little hands. The fashion blogosphere has become a forum for instant feedback; criticism and praise are dished out hard and fast from all the corners of the world.

Most importantly, however, the fashion world has the singular ability to dictate what the consumer should consume. Without Vogue, Bazaar, and GQ, most of us wouldn't have a clue what to spend our allowance on. It is not just about clothing. What we wear is a powerful signifier of our identity. It embodies who we are and who we aspire to be, and it is an idea as old as humanity itself. In Ancient Rome, only a citizen was permitted to wear the toga, a garment that afforded the wearer the protection of the empire regardless of where he went. In Tudor England, during a period of unprecedented social mobility, the Sumptuary Laws maintained hierarchies by controlling what fashions could be worn by persons of various ranks. Throughout history, clothing has determined identity: to be a member of any group, any household or guild, one donned the appropriate livery.

Curiously, the word 'livery' had a double meaning. It comes from the Old French livrance, which meant delivery or handing over from master to man, the clothing that constituted his payment and visually marked his subordination. It also suggests deliverance, since the man who bought his livery literally bought his own freedom. Thus, the concept of livery comprised both a person's servitude and her liberty from it. It is an idea worth reflecting upon especially in this time when a hunger for fashion can compel young women to distort, starve or prostitute themselves; when a unique vision, an eye for beauty, or quirky personal style can turn a high school student into a shoe designer or a 13 year-old into a fashion authority. If it can simultaneously enslave and free us, then fashion must command our respect, and paradoxically, our irreverence.